L'ÉCOLE DE WATTEAU

Although the term "École de Watteau" is applied to paintings by Pater, Lancret, Mercier, and other followers, it also is applied to artists whose works have a kinship with the master's work but, generally, cannot be linked to a named painter. Yet these anonymous figures have left behind considerable oeuvres that are worthy of further study.

Although the term "École de Watteau" is applied to paintings by Pater, Lancret, Mercier, and other followers, it also is applied to artists whose works have a kinship with the master's work but, generally, cannot be linked to a named painter. Yet these anonymous figures have left behind considerable oeuvres that are worthy of further study.

TWO PASTORAL IDYLLS BY WATTEAU

Watteau’s sensitivity as a plein-air draftsman is recorded in two very small, newly rediscovered drawings by him. They remind us that his painted fêtes galantes, as ethereal as they may seem, also reflect the actuality of his time.

Watteau’s sensitivity as a plein-air draftsman is recorded in two very small, newly rediscovered drawings by him. They remind us that his painted fêtes galantes, as ethereal as they may seem, also reflect the actuality of his time.

JACQUES VIGOUREUX DUPLESSIS AND CHINOISERIE

Working in the first three decades of the eighteenth century, Jacques Vigoureux Duplessis was a talented and prolific painter of chinoiserie subjects. In addition to traditional easel pictures, he turned his attention to screens and other decorative arts that often bear similarities to the work of Claude III Audran and Claude Gillot.

MORE ON THE OCTAVIEN BROTHERS

The oeuvres of François Octavien and his brother prove to be more extensive and varied than had been thought. In addition to fêtes galantes, there are domestic subjects and even erotic scenes. At the same time, there are a great many paintings wrongly attributed to the two artists that have confused our understanding of their work.

The oeuvres of François Octavien and his brother prove to be more extensive and varied than had been thought. In addition to fêtes galantes, there are domestic subjects and even erotic scenes. At the same time, there are a great many paintings wrongly attributed to the two artists that have confused our understanding of their work.

THE OCTAVIEN BROTHERS

François Octavien and his younger brother, who bore the very same name, painted fêtes galantes and other rococo subjects in the wake of Watteau. The elder brother, undoubtedly the more talented of the two, rarely extended beyond what other Watteau satellites painted. Nonetheless, the works of the Octavien brothers are more numerous than might have been thought and help fill out our sense of art production in Paris in the first third of the eighteenth century.

François Octavien and his younger brother, who bore the very same name, painted fêtes galantes and other rococo subjects in the wake of Watteau. The elder brother, undoubtedly the more talented of the two, rarely extended beyond what other Watteau satellites painted. Nonetheless, the works of the Octavien brothers are more numerous than might have been thought and help fill out our sense of art production in Paris in the first third of the eighteenth century.

QUILLARD’S JOURNEY TO PORTUGAL

When Quillard traveled to Portugal—a turning point in his career—he did so in the company of a Swiss naturalist, Dr. Charles Fréderic Merveilleux. It has been overlooked that Merveileux wrote an account of his travels and that he occasionally referred to the painter. These constitute the only first-hand observations of Quillard, whose career was cut short just a few years later.

When Quillard traveled to Portugal—a turning point in his career—he did so in the company of a Swiss naturalist, Dr. Charles Fréderic Merveilleux. It has been overlooked that Merveileux wrote an account of his travels and that he occasionally referred to the painter. These constitute the only first-hand observations of Quillard, whose career was cut short just a few years later.

DRAWINGS BY THE YOUNG QUILLARD

Quillard’s early drawings show a remarkable uniformity of style and purpose. Many copy ideas taken from Watteau or are variations on those borrowings. Despite the coherence of the group, some scholars have sought to re-attribute them to Pater, Watteau, or other artists, but these attempts remain unconvincing.

Quillard’s early drawings show a remarkable uniformity of style and purpose. Many copy ideas taken from Watteau or are variations on those borrowings. Despite the coherence of the group, some scholars have sought to re-attribute them to Pater, Watteau, or other artists, but these attempts remain unconvincing.

EXPANDING QUILLARD’S OEUVRE

Essentially unknown a century ago, the oeuvre of Pierre Antoine Quillard (c. 1704-1733) grew as paintings were discovered in Paris, Lisbon, St. Petersburg, and other European capitals. This study brings together an additional nine works from equally diverse locations that have not been presented publicly or have not been identified with him. They shed light on a distinctive aspect of his studio practice, namely replicating whole or partial portions of his compositions.

Essentially unknown a century ago, the oeuvre of Pierre Antoine Quillard (c. 1704-1733) grew as paintings were discovered in Paris, Lisbon, St. Petersburg, and other European capitals. This study brings together an additional nine works from equally diverse locations that have not been presented publicly or have not been identified with him. They shed light on a distinctive aspect of his studio practice, namely replicating whole or partial portions of his compositions.

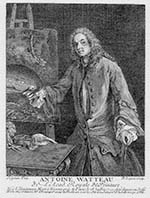

WATTEAU, PEINTRE DE FÊTES GALANTES

Watteau’s most famous and beautiful paintings are called “fêtes galantes” yet until the very late 19th century, it was not customary to call them by that name. Had it not been for the mistaken belief that he was received into the Academy with the title “painter of fêtes glantes,” the term might never have become as customary as it is today.

Watteau’s most famous and beautiful paintings are called “fêtes galantes” yet until the very late 19th century, it was not customary to call them by that name. Had it not been for the mistaken belief that he was received into the Academy with the title “painter of fêtes glantes,” the term might never have become as customary as it is today.

DEATH AT AGE THIRTY-SEVEN

One is accustomed to read that Watteau died when he was only thirty-seven years old. Actually, the artist died several months before his thirty-seventh birthday. But in the obituary written by one of his good friends, Antoine de la Roque, editor of the Mercure, the author finessed his age slightly to aid a parallel between Watteau’s and Raphael’s deaths.

One is accustomed to read that Watteau died when he was only thirty-seven years old. Actually, the artist died several months before his thirty-seventh birthday. But in the obituary written by one of his good friends, Antoine de la Roque, editor of the Mercure, the author finessed his age slightly to aid a parallel between Watteau’s and Raphael’s deaths.

RECONSIDERING THE BEAUVAIS WORKSHOP’S PREMIÈRE TENTURE CHINOISE

In the late seventeenth century the Beauvais workshop created a cycle of nine tapestries celebrating the life of the Emperor of China. La Première tenture chinoise, as it is known, includes scenes of imperial receptions, banqueting, boating, and harvesting. While seemingly fanciful, many of the elements depicted are accurate and prove to be based on imagery found in contemporary books describing travel in the Far East.

In the late seventeenth century the Beauvais workshop created a cycle of nine tapestries celebrating the life of the Emperor of China. La Première tenture chinoise, as it is known, includes scenes of imperial receptions, banqueting, boating, and harvesting. While seemingly fanciful, many of the elements depicted are accurate and prove to be based on imagery found in contemporary books describing travel in the Far East.

JEAN JACQUES SPOEDE, GILLOT'S FORGOTTEN ASSISTANT AND WATTEAU'S SPECIAL FRIEND

Jean Jacques Spoede was described at the time to be Watteau’s “ami particulier.” A cycle of almost forty drawings of theatrical characters by Spoede and some scattered drawings by the young Watteau have much in common. Both artists’ works can be traced to inventions by Claude Gillot, and the evidence suggests that both men had been students or assistants in Gillot’s atelier. Much of their later art was indebted to this crucial moment in their respective careers.

Jean Jacques Spoede was described at the time to be Watteau’s “ami particulier.” A cycle of almost forty drawings of theatrical characters by Spoede and some scattered drawings by the young Watteau have much in common. Both artists’ works can be traced to inventions by Claude Gillot, and the evidence suggests that both men had been students or assistants in Gillot’s atelier. Much of their later art was indebted to this crucial moment in their respective careers.

TWO NEW WATTEAU DRAWINGS

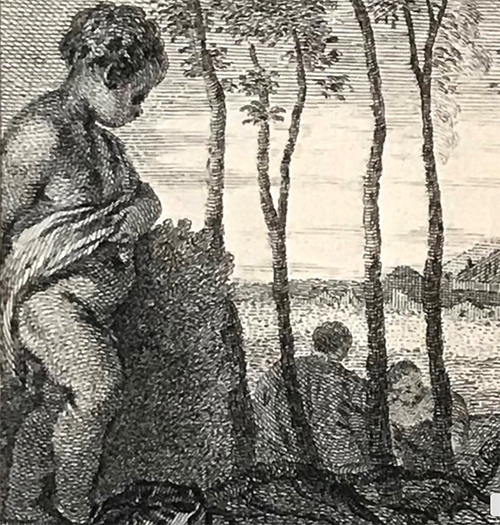

The corpus of known Watteau drawings continues to expand. This study introduces two unknown drawings. One is a charming study of cats; the other is Watteau’s copy after a landscape by the Venetian Renaissance artist, Domenico Campagnola. Martin Eidelberg and Axel Moulinier co-author this fascinating discovery.

The corpus of known Watteau drawings continues to expand. This study introduces two unknown drawings. One is a charming study of cats; the other is Watteau’s copy after a landscape by the Venetian Renaissance artist, Domenico Campagnola. Martin Eidelberg and Axel Moulinier co-author this fascinating discovery.

RECONSIDERING WATTEAU’S ENSEIGNE DE GERSAINT

Despite the extensive literature on the beautiful signboard that Watteau painted for his friend Edme Gersaint, there still is much to learn. Watteau was more responsive than we had realized to the tradition of signboards showing shop interiors. And, not least, the original format of the signboard needs to be reconsidered.

Despite the extensive literature on the beautiful signboard that Watteau painted for his friend Edme Gersaint, there still is much to learn. Watteau was more responsive than we had realized to the tradition of signboards showing shop interiors. And, not least, the original format of the signboard needs to be reconsidered.

THE JOVIAL MASTER

Among the many anonymous painters who emulated Watteau, one stands out for his robust and humorous spirit—an artist we have named “The Jovial Master.” Six works have been gathered together here. Some are old misattributed friends in the Watteau literature, some are new discoveries, but all have the same spirit of mirth and vitality.

Among the many anonymous painters who emulated Watteau, one stands out for his robust and humorous spirit—an artist we have named “The Jovial Master.” Six works have been gathered together here. Some are old misattributed friends in the Watteau literature, some are new discoveries, but all have the same spirit of mirth and vitality.

WATTEAU’S FORGOTTEN FRIEND: JEAN NICOLAS DE LA HIRE

Entirely forgotten today, the doctor and botanist Jean Nicolas de la Hire not only emulated Watteau's art but he also was the painter's friend. All that remains of his work, however, are some descriptions and engravings, which are brought together here.

Entirely forgotten today, the doctor and botanist Jean Nicolas de la Hire not only emulated Watteau's art but he also was the painter's friend. All that remains of his work, however, are some descriptions and engravings, which are brought together here.

A WATTEAU DRAWING REDISCOVERED

A red chalk drawing of a standing mother and child, now in the Johnson Museum of Cornell University, had been lost sight of until now. It has an unsuspected, century-long history of being associated with Watteau and Lancret. While it is one of a pair of drawings, only this one proves to be by Watteau himself.

A red chalk drawing of a standing mother and child, now in the Johnson Museum of Cornell University, had been lost sight of until now. It has an unsuspected, century-long history of being associated with Watteau and Lancret. While it is one of a pair of drawings, only this one proves to be by Watteau himself.

WATTEAU AND A SOUVENIR OF ROME

It has become increasingly clear that Watteau intentionally inserted Italian elements in his French fêtes galantes, often depicting Ancient and modern buildings that could be seen in Rome. La Contredanse, now in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, depicts a statue of a urinating boy that in his time was in Rome and was thought to be a Classical work. How Watteau came to know this sculpture, even if only indirectly, involves Rubens and Antoine Crozat in an intriguing triangle.

It has become increasingly clear that Watteau intentionally inserted Italian elements in his French fêtes galantes, often depicting Ancient and modern buildings that could be seen in Rome. La Contredanse, now in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, depicts a statue of a urinating boy that in his time was in Rome and was thought to be a Classical work. How Watteau came to know this sculpture, even if only indirectly, involves Rubens and Antoine Crozat in an intriguing triangle.

THE YOUNG LANCRET AND WATTEAU

Nicolas Lancret was one of Watteau’s most important followers. As the evidence suggests, he served for a brief time as Watteau’s assistant, helping to compose and paint the Portrait of Antoine de La Roque. At the same time, Lancret worked as an independent artist, creating fêtes galantes in the style of his master. Some were taken to be by Watteau himself, which angered Watteau, and the resulting rivalry contributed to the breakup of their relationship. Even today, a number of pictures wrongly attributed to Watteau prove to be by Lancret, painted while he was under his master’s influence.

Nicolas Lancret was one of Watteau’s most important followers. As the evidence suggests, he served for a brief time as Watteau’s assistant, helping to compose and paint the Portrait of Antoine de La Roque. At the same time, Lancret worked as an independent artist, creating fêtes galantes in the style of his master. Some were taken to be by Watteau himself, which angered Watteau, and the resulting rivalry contributed to the breakup of their relationship. Even today, a number of pictures wrongly attributed to Watteau prove to be by Lancret, painted while he was under his master’s influence.

THE NANTES MASTER

Among the many French painters that followed in Watteau’s wake, one charming artist can now be recognized in his own right. We have named him the Nantes Master after two of his works that are in that city’s museum. Although still without his true name, we can establish something of his oeuvre but cannot chart his career. If his works have long been hidden under the names of Lancret, Pater, and Octavien, now his works can be recognized in their own right.

Among the many French painters that followed in Watteau’s wake, one charming artist can now be recognized in his own right. We have named him the Nantes Master after two of his works that are in that city’s museum. Although still without his true name, we can establish something of his oeuvre but cannot chart his career. If his works have long been hidden under the names of Lancret, Pater, and Octavien, now his works can be recognized in their own right.

PHILIPPE MERCIER AND THE MILES MASTER

A fête galante previously considered to be Philippe Mercier’s earliest work, painted while he was still in Germany, c. 1715-16, is here attributed to an anonymous painter whom I have identified as the Miles Master. Seven additional paintings, almost all previously attributed to Watteau or his school, can be identified. The artist was active c. 1725-40 and reflects the innovations of Parisian painting, yet he was probably not French but German or Netherlandish.

A fête galante previously considered to be Philippe Mercier’s earliest work, painted while he was still in Germany, c. 1715-16, is here attributed to an anonymous painter whom I have identified as the Miles Master. Seven additional paintings, almost all previously attributed to Watteau or his school, can be identified. The artist was active c. 1725-40 and reflects the innovations of Parisian painting, yet he was probably not French but German or Netherlandish.

PHILIPPE MERCIER, WATTEAU'S ENGLISH FOLLOWER

The relationship that existed between Watteau and Philippe Mercier has not been properly studied, yet it is of importance for our understanding of both artists’ careers. A close analysis of Mercier’s early paintings demonstrates that he knew Watteau in Paris c. 1715, and that he profited greatly from that experience. A consideration of Mercier’s early career also reveals that he is not the author of many of the paintings that are popularly credited to him.

The relationship that existed between Watteau and Philippe Mercier has not been properly studied, yet it is of importance for our understanding of both artists’ careers. A close analysis of Mercier’s early paintings demonstrates that he knew Watteau in Paris c. 1715, and that he profited greatly from that experience. A consideration of Mercier’s early career also reveals that he is not the author of many of the paintings that are popularly credited to him.

DEFINING THE OEUVRE OF BONAVENTURE DE BAR (Part 3)

Surprisingly, only one extant and essentially unpublished drawing can safely be attributed to Bonaventure de Bar. There are textual references to several sold in the eighteenth century and to several sold in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. On the other hand, most drawings that have been associated with this artist prove to be spurious attributions.

DEFINING THE OEUVRE OF BONAVENTURE DE BAR (Part 2)

Whereas de Bar's oeuvre is limited to a handful of actual paintings, over a hundred other pictures have wrongly been attributed to him. This disproportionate number of works has clouded our sense of de Bar's true artistic personality. More than half of them are copies after compositions by Watteau, Lancret and Pater, but none are by de Bar. Some wrongly attributed works prove to be by Quillard, Angellis, Ollivier, and other Watteau satellites, but many are left in the limbo of anonymity.

Whereas de Bar's oeuvre is limited to a handful of actual paintings, over a hundred other pictures have wrongly been attributed to him. This disproportionate number of works has clouded our sense of de Bar's true artistic personality. More than half of them are copies after compositions by Watteau, Lancret and Pater, but none are by de Bar. Some wrongly attributed works prove to be by Quillard, Angellis, Ollivier, and other Watteau satellites, but many are left in the limbo of anonymity.

DEFINING THE OEUVRE OF BONAVENTURE DE BAR (Part 1)

Bonaventure de Bar (1700-1729) is one of the least studied of Watteau's so-called satellites. This essay identifies twelve extant paintings that can be attributed to him, many of which can be documented to the eighteenth century. Also considered are references to a dozen other de Bar paintings mentioned in eighteenth-century auction catalogues. When brought together, this material reveals an accomplished artist with a consistent, recognizable, and engaging style.

Bonaventure de Bar (1700-1729) is one of the least studied of Watteau's so-called satellites. This essay identifies twelve extant paintings that can be attributed to him, many of which can be documented to the eighteenth century. Also considered are references to a dozen other de Bar paintings mentioned in eighteenth-century auction catalogues. When brought together, this material reveals an accomplished artist with a consistent, recognizable, and engaging style.

VLEUGHELS' CIRCLE OF FRIENDS IN THE EARLY EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Letters written between 1715 and 1732 by Nicolas Vleughels to the abate Giovanni Antonio Grassetti of Modena shed light on Vleughels’ circle of friends and his travels in Italy. This essay focuses on Vleughels’ first stay in the South, from 1704 to 1715, and several of the years after his return to Paris. It relies on these letters as well as his drawings and occasional references in the correspondence of Rosalba Carriera to document more firmly his travels throughout Italy, which prove more extensive than had previously been thought. It also allows us to gain some insight into his relation with the maecenas Pierre Crozat and the sculptor Pierre Legros, and poses some questions about his association with Watteau.

Letters written between 1715 and 1732 by Nicolas Vleughels to the abate Giovanni Antonio Grassetti of Modena shed light on Vleughels’ circle of friends and his travels in Italy. This essay focuses on Vleughels’ first stay in the South, from 1704 to 1715, and several of the years after his return to Paris. It relies on these letters as well as his drawings and occasional references in the correspondence of Rosalba Carriera to document more firmly his travels throughout Italy, which prove more extensive than had previously been thought. It also allows us to gain some insight into his relation with the maecenas Pierre Crozat and the sculptor Pierre Legros, and poses some questions about his association with Watteau.

THE SIESTE MASTER

La Sieste, a painting formerly attributed to Philip Mercier, and most recently to Pierre Antoine Quillard, proves to be by the same hand as a drawing in the Musée des beaux-arts of Grenoble. I have named this otherwise unidentified artist the Sieste Master.

La Sieste, a painting formerly attributed to Philip Mercier, and most recently to Pierre Antoine Quillard, proves to be by the same hand as a drawing in the Musée des beaux-arts of Grenoble. I have named this otherwise unidentified artist the Sieste Master.

WATTEAU'S LANDSCAPES OF THE ENVIRONS OF ROME AND VENICE

Among the hundreds of Watteau drawings in Jean de Jullienne’s collection were twenty-four Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice. Nine of these are extant and, despite a recent challenge, their association with Jullienne’s set seems justifiable on both historical and stylistic grounds. They stem from his friendship with Nicolas Vleughels and are linked with his copies after drawings by Campagnola, Rubens, and Van Dyck. Taken together, these several sets of studies create a context that brings the artist together not only with Vleughels but also with Crozat and the comte de Caylus.

Among the hundreds of Watteau drawings in Jean de Jullienne’s collection were twenty-four Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice. Nine of these are extant and, despite a recent challenge, their association with Jullienne’s set seems justifiable on both historical and stylistic grounds. They stem from his friendship with Nicolas Vleughels and are linked with his copies after drawings by Campagnola, Rubens, and Van Dyck. Taken together, these several sets of studies create a context that brings the artist together not only with Vleughels but also with Crozat and the comte de Caylus.

ASSIS AUPRÈS DE TOI, WATTEAU AND JULLIENNE IMMORTALIZED

.jpg) A wonderful double portrait of Watteau painting and Jean de Jullienne playing the base viol serves as the frontispiece of Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, the two volumes of engravings after Watteau’s paintings. For almost a century, scholars have wrongly maintained that the composition was Jullienne’s invention, not Watteau’s, but this study shows that the engraving does reflect an authentic Watteau painting. Additionally, attention is drawn to a lost Watteau landscape painting that was in Jullienne’s collection.

A wonderful double portrait of Watteau painting and Jean de Jullienne playing the base viol serves as the frontispiece of Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, the two volumes of engravings after Watteau’s paintings. For almost a century, scholars have wrongly maintained that the composition was Jullienne’s invention, not Watteau’s, but this study shows that the engraving does reflect an authentic Watteau painting. Additionally, attention is drawn to a lost Watteau landscape painting that was in Jullienne’s collection.