TWO PASTORAL IDYLLS BY WATTEAU

© Martin Eidelberg

Created September 2023

© Martin Eidelberg

Created September 2023

The opening words of the Goncourt brothers’ brilliant essay on Watteau describe how the artist portrayed an imaginary, halcyon existence in his fêtes galantes:

The great poet of the eighteenth century is Watteau. A world, an entire world of poetry and fantasy, issuing from his mind, filled his art with the elegance of a supernatural life. An enchantment, a thousand enchantments arose, upon wings, from the whims of his brain, from the humours of his artistic practice, from the absolute originality of his genius. He drew magical visions, an ideal world, from his imagination and raised up, beyond the frontiers of his epoch . . . .1

The Goncourts took delight in basking in the sunlight of a world far removed from their century’s often grim reality. They much preferred dreaming about the pleasures of a courtly society rather than accepting the reality of a world dominated by urban bankers and industrialists. But what about Watteau? To what degree was he solely a poet, painting “the whims of his brain”? Was he also, to some degree, selectively recording the actuality of his time?

|

|

|

private collection. |

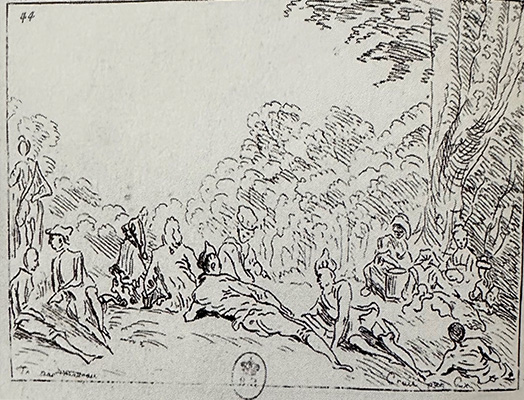

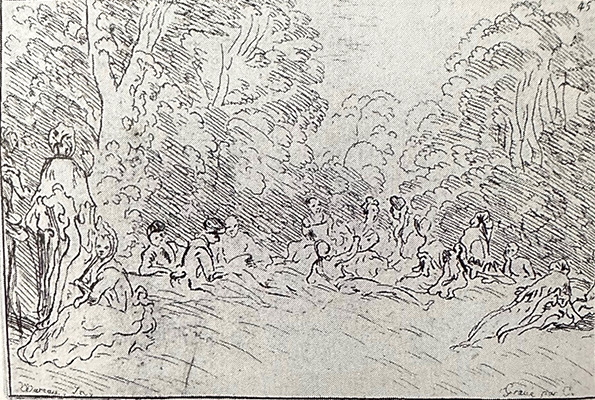

Two small Watteau drawings depicting elegantly dressed figures dispersed across a lush meadow prompt the question of whether the artist drew his subject from life or whether these scenes were conceived in his “fertile imagination” (figs. 1, 2). Although they have not been seen publicly for a half century, these two drawings have a noteworthy history.

|

|

| 3. Anne Claude de Tubières, comte de Caylus, after Watteau, Figures Reclining in a Meadow, etching.

|

4. Anne Claude de Tubières, comte de Caylus, after Watteau, Figures Reclining in a Meadow, etching. |

The two drawings were etched by Watteau’s close friend and biographer, the comte de Caylus (1692-1765). A committed amateur of the arts, he was eager to gain skill as a print maker—an avocation he was just learning. He successfully replicated drawings by Watteau, Gillot, and other contemporary French artists, as well as drawings by Italian Old Masters. Caylus prepared these etchings in Watteau’s lifetime or shortly thereafter, probably in the 1710s or ‘20s. Regrettably, we do not know who owned these drawings at that time; was it Caylus himself, Jean de Jullienne, or someone else in their circle? Caylus' etchings are also of interest because they show that the extant drawing have been trimmed ever so slightly at the sides.

The two Watteau drawings cannot be traced to the later eighteenth century, nor are they identifiable in nineteenth-century records. They re-emerged after World War I, still together, and were subsequently owned by various private collectors in Paris, London, and New York.2 They were last seen together was in a sale in New York in 1974 when they were bought by Hans J. Morgenthau (1904-1980). They remained in New York with the Morgenthau family for the past half century and only just recently were sold to a prominent Los Angeles collector.

A remarkable aspect of these drawings is their small scale, despite their containing a multitude of figures. They measure little more than 9 x 13 cm, yet each features more than a dozen people—men and women, the majority seated or reclining on the grass, a few standing. In effect, they form miniature fêtes galantes. Although they are exceedingly small and just cursorily indicated, they resemble the exquisite figures that Watteau painted in his larger fêtes galantes. As the Goncourt brothers so eloquently described the paintings:

All the fascination of women in repose: the languor, the idleness, the abandonment, the mutual leanings upon one another, outstretched limbs, the indolence, the harmony of attitudes . . . the meanderings, the undulations, the pliancies of a woman’s body; the play of slender fingers upon the handle of a fan, the indiscretion of high heels peeping below the skirt, the chance felicities of demeanour, the coquetry of gesture, the manoeuvering of shoulders, and all that erudition, that mime of grace, which the women of the preceding century acquired from their mirrors; all this lives on in Watteau.3

|

| 5. Watteau, Figures Reclining in a Meadow (detail). |

All of the Goncourt brothers’ rhapsodic prose was directed toward the artist’s paintings but it could equally be applied to the figures drawn here in red chalk. The languor, the idleness, the coquetry of gesture—they are all captured here. The two women in the right foreground of the second drawing encapsulate the delicate emotions that Watteau was able to infuse into his canvases—the poignant, seated woman with her fan brought to her lips, the standing woman turned away from us, hiding her sentiments and thoughts (fig. 5).

But what are these drawings? Are they sketches from life or were they conceived in the artist’s imagination as preparatory designs for paintings? Although we cannot be absolutely sure, they most probably were made from life, viewed on site.

|

|

6. Watteau, View of the Porcherons, red chalk, 8.5 x 14.3 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

7. Watteau, View of the Porcherons, red chalk, 8.7 x 14.2 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

One indication that these compositions were drawn in an actual park is their diminutive size. Their small scale recalls two equally diminutive drawings of farms now in the Metropolitan Museum—each measuring only millimeters less than the two in California (figs. 6, 7).4 The artist apparently favored small notebooks for fresh air excursions.5 The Metropolitan Museum landscapes may well be a key to understanding the two sketches in California.

|

| 8. Watteau, La Promenade sur les remparts (detail), oil on canvas. Los Angeles, Ariane and Lionel Sauvage collection. |

In these two drawings the majority of the figures sit directly on the grass, and only a few stand, generally at the side. As others have noted, the arrangement of this assembly recalls the group of fashionable people populating the foreground of Watteau’s La Promenade sur les remparts (fig. 8).

|

| 9. Watteau, Divertissements champêtres (detail), oil on canvas. London, Wallace Collection. |

Watteau painted such groups in his other fêtes, especially in the middle grounds of his pictures, as in his Divertissements champêtres (fig. 9).

|

|

Although Watteau studied the real world, he escaped its limitations. How different his paintings are from those of the next generation, such as The Reading Party by Jean François de Troy (fig. 10).6 Although de Troy (1679-1752) was five years older than Watteau, his mature works, painted a decade or more after Watteau’s death, exhibit a material, earth-bound realism. By contrast, the Goncourt brothers well captured the ethereal quality of Watteau’s vision:

And upon what a stage he produced it, amid what natural prospects, fit setting for a halcyon existence, the painter aired his thoughts. Here is a region that conspires with his mood—amorous woods, meadows overflowing with music . . . . It is as if the scissors of some couturier of genius, playfully manipulated the negligence of négligé, the essential finesse of finery, the sweet disorder of the morning, and the ordered elegance of the afternoon. . . .This inspired tailor was also a marvellous Utopian, an embroiderer of all things. The most pleasant and the most obstinate romancer.7

As inspired a Utopian as he may have been, these two small drawings remind us that Watteau also was an observant witness to the people and customs of his actual world. Yet his lyrical renderings also elevated reality into an intriguing alternative realm.

NOTES

1 Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, French XVIII Century Painters, trans. Robin Ironside (New York: 1948), 1.

2 Paris, collection François Flameng (1856-1923); his sale, Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, May 26-27, 1919, lot 169; Paris, collection of Walter Gay; Paris, with Jacques Mathey; London, with Hans Maximilian Calmann in 1948; New York, collection of Mrs. Alan L. Corey; her sale, New York, Sotheby Parke-Bernet, December 5-7, 1974, lot 546; sold to Hans Morgenthau. The two drawings are listed in Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996), 1, cat. 70, 71, with the mention “localisation actuelle inconnue.”

3 Goncourt, French XVIII Century Painters, 2.

4 Rosenberg and Prat. Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 1: cat. 235, 236.

5 This is not to claim that Watteau used such small sheets only when he was outside his studio. Quite the contrary. In his early career he frequently drew single figures in this small format; see Rosenberg and Prat. Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 1: cat. 9, 27, 29-32, 35-44, 46-50, 53-55. Others are equally small studies but their versos show fragments of larger compositions, indicating that the sheets were formerly larger; see cat. 28, 45.

6 Sold London, Christie’s, December 8, 2022, lot 28.

7 Goncourt, French XVIII Century Painters, 2-5.