WATTEAU’S LANDSCAPES OF THE ENVIRONS OF ROME AND VENICE

© Martin Eidelberg

Created February 17, 2011

Click to Print or Download PDF Version

Among the hundreds of Watteau drawings belonging to Jean de Jullienne, the artist’s friend and patron, were twenty-four views of Italian sites. The series was divided into two lots in the 1767 sale of Jullienne’s collection:

825. Fourteen landscape drawings of the environs of Rome & Venice.

826. Ten others, and a leopard.1

The extensive nature of this group is surprising because it includes not just the fourteen in the first lot—all that has normally been cited until now--but twenty-four, as is indicated by the second lot of “ten others.”

As far back as 1931, Parker signaled three extant drawings that he believed came from this set.2 At that time, other experts were less perspicacious; drawings from this series frequently went unrecognized and their attribution to Watteau was left uncertain.3 Parker and Mathey’s catalogue raisonné of Watteau drawings brought together many Italian views--some topographical and others of a more fantastic nature. These authors rightly associated seven extant sanguine drawings with the Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice, an opinion subsequently shared by most scholars.4 Unfortunately, it was also apparent that Parker and Mathey had been far too inclusive and many of the other Italianate scenes that they accepted cannot be from Watteau’s hand. Rosenberg and Prat’s recent catalogue of Watteau’s drawings cast away much of that chaff, but these scholars then veered in the opposite direction and rejected autograph drawings as well. Amongst them are all the sheets that previously were associated with Jullienne’s Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice, thereby creating the issue that I wish to address here.5

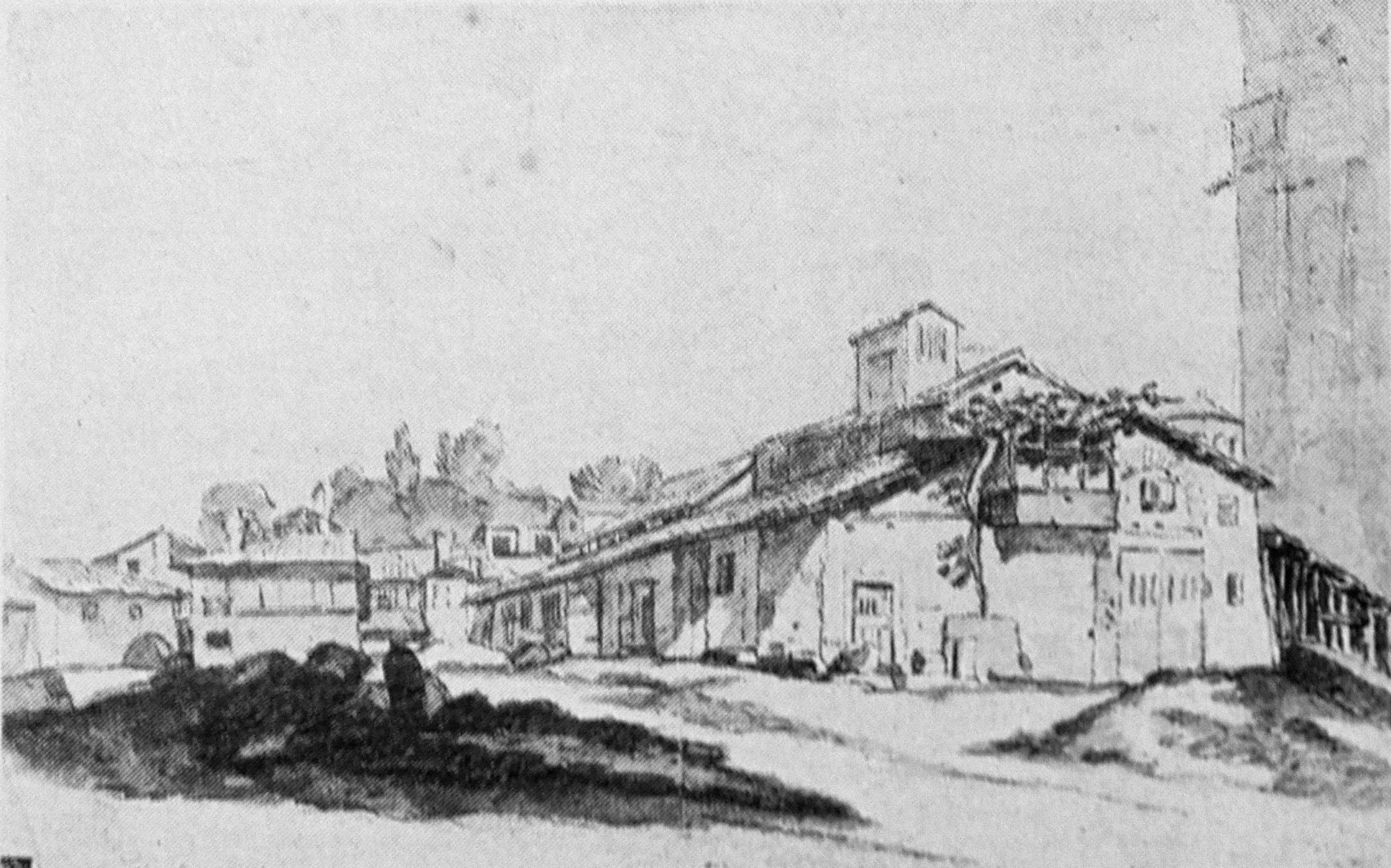

1. Antoine Watteau after Nicolas Vleughels, A View of Rome near St. Peter’s, sanguine, 12.5 x 18.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

2. Watteau after Vleughels, A View of Rome behind St. Peter’s, sanguine counterproof, 10 x 14 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

3. Watteau after Vleughels, A View of Bassano, sanguine, 13 x 18.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

4. Watteau after Vleughels, A View of Padua with the Ponte San Giovanni, sanguine counterproof, 14.3 x 16.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

5. Watteau after Vleughels, A View of Padua with the Ponte Tadi, sanguine counterproof, 11.3 x 19.4 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

6. Watteau after Vleughels, A View of Padua, sanguine, 12.4 x 17.5 cm. Grenoble, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

When first Parker, and then Parker and Mathey, assembled the series, they were swayed by the fact that each of the selected drawings was inscribed with the name of the locale, and these fit with the Jullienne listing. Two are of Rome (figs. 1 and 2) and, while none show Venice itself, five are of cities within the Venetian Republic: one of Bassano (fig. 3) and the remainder of Padua (figs. 4-5). Subsequently, Rosenberg and Prat located yet another two views of Padua (fig. 6).6 These nine drawings are relatively comparable in size, measuring about 13 by 19 cm; some are slightly smaller due to evident trimming. Equally important, they demonstrate a uniformity of draftsmanship. All are rendered in sanguine chalk applied in a strong, emphatic way. Most noticeable are the unfaltering, evenly drawn vertical strokes that define the walls of buildings and the sides of cliffs. All the cities are named in the same distinctive script and, except in one instance, the identifying label is at the top of the page. Numerically, these nine sheets (even if many are only counterproofs) constitute just slightly more than a third of the total listed in the Jullienne 1767 catalogue.7

|

|

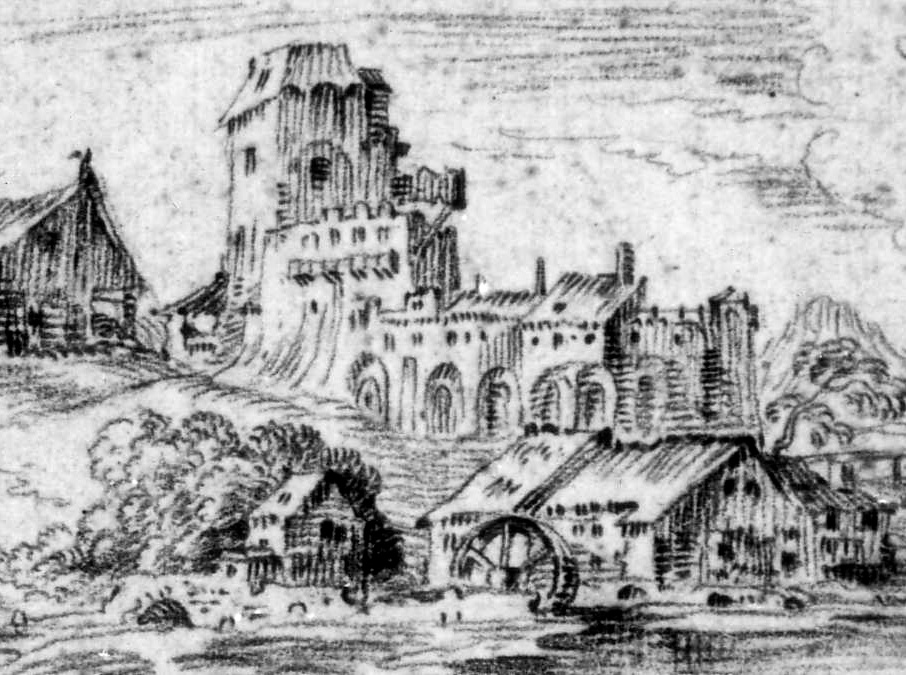

7. Vleughels, A View of Rome showing the Houses Behind St. Peter’s, 1708, 18.8 x 29.3 cm. London, British Museum. |

8. Vleughels, A View of Bassano, black chalk and ink wash, 20 x 26.4 cm. Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts. |

There is a second, related set of drawings depicting the environs of Rome and Venice, but by a decidedly different hand and rendered in different mediums. One is a sanguine and wash drawing inscribed “Dessiné derrière St Pierre le 30 may 1708” (fig. 7). Another such landscape study, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Dijon, is labeled “a Bassanau le 24du aout 1707” (fig. 8).8 A third, showing the courtyard of a farm in Bassano, is also dated 1707.9 These drawings are linked in several ways: stylistically, by the format of their inscriptions, their mediums (chalk and wash), and their comparable sizes.

The inscriptions on these three drawings, designating both the place and date, indicate that the artist executed them on site. This naturally precludes Watteau who never visited Italy. Even though Parker and Mathey wrongly attributed to Watteau the first sheet, the May 1708 study made behind St. Peter’s (fig. 7), Denys Sutton had already associated it with Watteau’s good friend, Nicolas Vleughels.10 Most scholars have since concurred.11 Indeed, Vleughels traveled in Italy for over a decade, beginning in late 1702 or early 1703 and staying until 1715. He spent much of his time in Rome and Venice, as well as in Correggio, Piacenza, Padua, Bologna, Bassano, and Modena.12 He apparently was accustomed to record the picturesque sites he visited, even if only a few of his drawings from that first Italian trip have been identified or survive.13

From the start, Parker opined that Jullienne’s drawings “must obviously be copies, though it remains doubtful from what models they were actually taken.”14 Although Watteau had expressed the desire to go to Italy, he never managed to do so. His Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice therefore must derive from a secondary source, such as drawings made by one of his several friends who had crossed the Alps. Philip Conisbee was the first to note the correspondence between Vleughels’ drawing of Bassano (fig. 8) and Watteau’s rendering of the same subject (fig. 3).15 This derivation has been accepted by other scholars without hesitation.16 Watteau worked on a smaller scale and in just sanguine chalk, but he remained a faithful copyist. He even transcribed Vleughels’ note naming the city but not the date since that, after all, would have been relevant only to Vleughels. Although this is the sole example of a one-to-one relationship, there are hints of others. Vleughels’ designation of another landscape being “dessiné derrière St Pierre” parallels the inscription on Watteau’s drawing of a country house as “derrière St Pierre” (figs. 2, 7), suggesting that Vleughels made several drawings behind St. Peter’s and that Watteau copied them. The obvious implication is that if Watteau transcribed one of Vleughels’ landscape drawings, then all twenty-four of his Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice were copied from studies made by his friend.

Vleughels returned to Paris in late March or early April of 1715, and he was agréé at the Académie Royale that summer.17 A letter he wrote on April 16 of that year to abaté Giovanni Antonio Grassetti in Modena confirms that his arrival in the French metropolis was recent.18 By then or soon thereafter, Vleughels and Watteau were lodged together in Pierre Crozat’s house. Watteau’s copies of Vleughels’ drawings must therefore date from 1715 or later, probably when the two men were guests of Pierre Crozat.

Our narrative could stop at this point were it not for the fact that in 1996 Rosenberg and Prat rejected Watteau’s authorship of the extant views of Rome, Bassano, and Padua. To their credit, Humphrey Wine and Margaret Morgan Grasselli objected to the exclusion of these drawings.19 More than a decade has passed and it is time to reconsider the question. Rosenberg and Prat’s objection to the drawings rested on stylistic grounds, although all that they specified was that the draftsmanship was too tight and mechanical, especially for drawings executed as late as c. 1717-19. Their imposition of a late dating of the drawings is in itself arbitrary since Watteau could have executed them soon after Vleughels’ return to Paris in 1715. Moreover, the constant quibbling about dating Watteau’s works to specific years seems a pointless diversion, especially since each scholar has his or her own chronology and rarely are the dates tied to specific, historical events.20

|

|

9. Watteau after Domenico Campagnola, Two Boys in a Landscape (detail), sanguine. Paris, Musée du Louvre. |

10. Watteau after Domenico Campagnola, Landscape (detail), sanguine. Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie. |

By what standard of tightness or freedom are these Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice being judged? Rather than comparing them to Watteau’s landscapes drawn from nature, although this could be favorably done, I would propose considering them with his copies after Titian’s and Campagnola’s landscapes (figs. 9 and 10).21 They share certain mannerisms of draftsmanship, not only the emphatic vertical strokes defining the walls but also, occasionally, areas of tight crosshatching. The way that Watteau used curving arcs to suggest the undulant rise and fall of the ground in his drawings after Vleughels’ landscapes have their counterparts in his copies after Titian and Campagnola; these arced lines were probably not in the Vleughels drawings, though they are in the Venetian designs, and Watteau’s insistent use of them in both series establishes the continuity between the two sets. Significantly, both of Watteau’s sets of copies were executed at roughly the same time, while Watteau and Vleughels were closely linked and were guests in Crozat’s house.

11. Watteau after Peter Paul Rubens, Head of Marie de Medici and a Hunter Blowing a Horn, sanguine and black chalk, 15.3 x 20.2 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

12. Watteau after Peter Paul Rubens, Head of a Devil, sanguine, 16.3 x 13.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

In the same way, we might compare the Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice with an extensive series of drawings of heads that Watteau executed after models by Rubens. Within the series, some sketches are modeled more softly (fig. 11), while others are rendered with stronger, more vibrant strokes (fig. 12). In making his copies, Watteau resorted to curving arcs, crosshatching, and other atypical elements in an attempt to emulate his models in a manner not unrelated to his copies after Vleughels’ Italian landscapes. Here again, while many of Watteau’s copies had originally been brought together by Parker and Mathey, Rosenberg and Prat rejected half of the series, claiming that there were too many stylistic divergences between the individual sheets.22 Yet even among the drawings that they do accept, such as the two sheets illustrated here, there are, as we have already noted, differences between them. Moreover, one must not disregard the circumstances under which these copies were made and the specific models that were being emulated.23

As I demonstrated elsewhere, Watteau’s studies of heads were copied not from Rubens’ paintings as had previously been proposed, but from a famous sketchbook then owned by Crozat, who had bought it directly from Ruben’s nephew.24 This sketchbook, with ninety-four expressive heads, was actually by one of Rubens’ shop assistants rather than by the master himself, but it was nonetheless a celebrated work in its day. Moreover, not only Watteau but also Vleughels copied pages of the Rubens sketchbook, the two artists sometimes copying the very same heads, perhaps even working side-by-side. In other words, the context in which Watteau made these copies after Rubens is closely aligned with his copying of Vleughels’ landscape drawings of Italy.

13. Watteau after Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony Van Dyck, Three Heads, 15 x21.3, sanguine and black chalk.Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentekabinet. |

One Watteau sheet related to this series, now in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 13), depicts at the right a head from the Rubens sketchbook, and at the left two smaller heads copied from a sheet of Van Dyck studies that was also owned by Crozat.25 Watteau copied at least one other head from this Van Dyck series, and perhaps not coincidentally, Watteau’s close friend and studio mate, the comte de Caylus, also made extensive copies of these same Van Dyck heads. Rosenberg and Prat reject the attribution of the Rijksmuseum drawing to Watteau, claiming that Caylus’ knowledge of the Van Dyck studies adds to the “ambiguity” of the attribution, and that an old, erroneous ascription on the mount to François Le Moyne is “proof” of the problematic nature of the drawing’s attribution. To the contrary, that Caylus knew the Van Dyck drawings helps affirm the ambience in which the Rijksmuseum drawing was made; that the drawing’s proper attribution was later forgotten is a situation that befalls many works of art and has no impact on the proper attribution. Once again, we are faced with the question that if the Rijksmuseum drawing is not by Watteau, then by whom is it? What other artist drew in this specifically Watteauesque manner, had access to Crozat’s collection, and was associated with both Vleughels and Caylus? Watteau alone is the artist who comfortably fits within this quadrumvirate.

Connoisseurship by itself always has the danger of being too subjective. One must not disregard compelling historical imperatives. If this consideration requires expanding our sense of Watteau’s style, then so be it. All these drawings—the studies after Titian and Campagnola, the Landscapes of Rome and Venice, the copies after the Rubens sketchbook, and the copies after Van Dyck sheets—shed much needed light on Watteau’s personal biography and stylistic maturation. They have significant implications for our understanding of Watteau’s oeuvre and his circle of friends.

NOTES

1. Sale, Paris, Jean de Jullienne collection, March 30-May 22, 1767: “ [Antoine Watteau] 825 Quatorze Desseins de paysage des environs de Rome & de Venise. 826 Dix autres, & un Léopard.” The first lot sold for 36 livres and the second brought 18.2 livres.

2. Karl T. Parker, The Drawings of Antoine Watteau (London: 1931), 18.

3. See, for example, the three drawings in the sale of the Groult collection, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, December 19, 1941, lots 98-100; they were not linked with the Jullienne series and they were classified only as “attribué à Jean-Antoine Watteau.” Similarly, a decade later a sheet with a view of Padua was rightly sold under Watteau’s name, but its relation to the Jullienne series still went unrecognized; sale, Paris, Galerie Charpentier, December 8, 1953, lot 29.

4. Karl T. Parker and Jacques Mathey, Catalogue complet de son oeuvre dessiné, 2 vols. (Paris: 1957-58), 1: 51, cat. nos. 377, 379, 381, 388, 390-92.

5. Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, 1684-1721, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996), 3: cat. nos. R 416, R553, R597, R628, R659-60, R618.

6. Rosenberg and Prat (hereafter “RP”), cat. nos. R194, R853.

7. Several other drawings of Italian sites, also in sanguine but slightly wider in format, are essentially identical in draftsmanship to the ones under discussion and probably should be given back to Watteau. These studies are somewhat more panoramic, which helps to explain their greater width. None are labeled in terms of the location depicted, which sets them apart from the nine that clearly were in the Jullienne series, but several can be identified as depicting Roman sites. The first (RP cat. no. R577) is a study of the buildings around the Torre delle Milizie, the second (RP cat. no. R829) depicts a church or monastery in the region, and a third (RP cat. no. R736) shows SS. Giovanni e Paolo. For seventeenth-century renderings of these Roman sites, see Per Bjurström, French Drawings: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Drawings in Swedish Public Collections, vol.2) (Stockholm: 1976), nos. 653 verso, 652 recto, 653 recto, respectively.

8. Cited by Jean-François Méjanès, Pierre-Charles Tremolières (Cholet: 1973), 93.

9. Rosenberg, “A propos de Nicolas Vleughels,” fig. 25.

10. Parker and Mathey, cat. no. 376; Denys Sutton, “Nicolas Vleughels (1668-1737),” Old Master Drawings 14 (1939-40), 52.

11. Pierre Rosenberg, “A propos de Nicolas Vleughels,” Pantheon 23 (1973), 143-53; Rosenberg and Prat, no. R218. The one notable exception is Bernard Hercenberg, Nicolas Vleughels, Peintre et directeur de l’Académie de France à Rome, 1668-1737 (Paris: 1975), 142-43.

12. Hercenberg, Nicolas Vleughels, 35-36, places the artist in Rome, Venice, and Modena. However, the artist was far more peripatetic. In a future study I will consider aspects of his early travels in Italy and his circle of friends there.

13. Vleughels’ landscape drawings from his second trip have similar notations identifying the place and date; see Hercenberg Nicolas Vleughels, cat. no. 325 (executed in Rome in 1725) and cat. no. 410 (in Orvieto in 1727). See also a 1731 study of the Campo Vaccino, Rome, which recently appeared in a sale at Pillet, November 30, 2008, lot 20. Vleughels’ drawings have not been sought or studied until recently, and it is probable that more of his topographical drawings await recognition.

14. Parker, The Drawings of Antoine Watteau, 18.

15. Philip Conisbee, “P.-C. Tremolière at Cholet,” Burlington Magazine 115 (October 1973), 700;

16. Marianne Roland Michel, Antoine Watteau, An Artist of the Eighteenth Century (New York: 1984),146-47; Margaret Morgan Grasselli, The Drawings of Antoine Watteau: Stylistic Development and Problems of Chronology (Ann Arbor, MI: 1987), 339-41, 530-31, cat. nos. 259-60; Eidelberg, “Watteau’s Italian Reveries,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, ser. 6, 126 (October 1995), 116-117.

17. Hercenberg, Vleughels, 36-37.

18. Busta E.V.6.1, Archivio Storico delle Fondazione Collegio di San Carlo, Modena. I am grateful to Dottoressa Enrica Manenti for her help many years ago in locating these documents. The letter was published by Giuseppe Campori, Lettere artistiche inedite (Modena: 1866), 156, but Campori misread the date as 1710.

19. See Humphrey Wine, Apollo 146 (November 1997), 59; Margaret Morgan Grasselli, Master Drawings 39 (Autumn 2001), 328.

20. Although Rosenberg and Prat’s catalogue imposes a tight chronology on Watteau’s drawings, one that forms the structure of the catalogue, it is noteworthy that they do not place any of Watteau’s landscape drawings in the latter part of the artist’s career. They assign the drawings after Campagnola (RP cat. nos. 430-34) to c. 1715-16. A beautiful study of a village or farm complex (RP cat. no. 435) is dated after 1715-16, and a fragmentary study of trees (RP cat. no. 575v) is dated 1717. Summary landscape elements appear in Watteau’s Finding of Moses (RP cat. no. 379) and study for Plaisirs d’amour (RP cat. no. 599), which are assigned dates of before 1716 and c. 1717-18. This is a very small number for the last six years of the artist’s life; none at all come from the last three years.

21. RP nos. 341-45, 432-434. Curiously, they classify the drawings as two separate groups, the first supposedly executed c. 1715 and the second c. 1715-16. Grasselli, Master Drawings (2001), 328, compared the Landscapes of the Environs of Rome and Venice with one of Watteau’s studies from nature (RP cat. no. 239), which is also compelling.

22. See RP nos. 240, 240bis, 241, 243, 350, 352, R4, R120, R225-26, R233, R235, R499, R502, R563, R568.

23. Apropos of the Head of a Devil (fig. 12), the previously unknown Rubensian source is a sheet now in the Biblioteca Reale, Turin; see Gianni Carlo Sciolla, I Disegni di maestri stranieri della Biblioteca Reale di Torino (Turin: 1974), no. 374.

24. Eidelberg, “An Album of Drawings from Rubens' Studio," Master Drawings 35 (Fall 1997), 234-66.

25. RP cat. no. R4. For my earlier analysis of this drawing, see Eidelberg, “An Album of Drawings from Rubens' Studio," 247, 254; also idem, "The Comte de Caylus’ Tête-à-tête with Van Dyck," Gazette des Beaux-Arts s.6, 140 (January 1998), 1-20; idem, “Some Etchings after Van Dyck by the Comte de Caylus,” On Paper 2 (March/April 1998), 12-17.